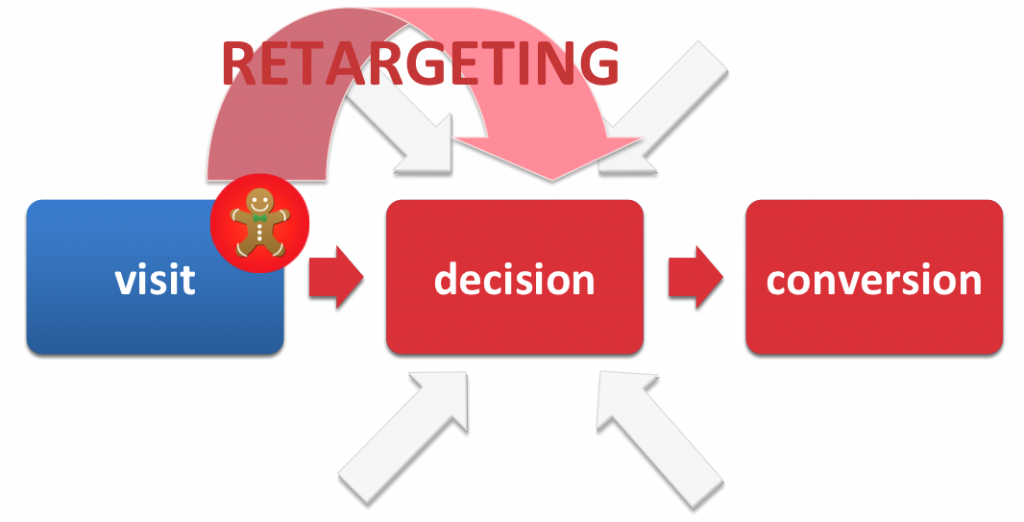

Remarketing is one of the most effective strategies in online marketing. By leveraging cookies and similar technologies, advertisers can direct their ads towards users who have previously visited their website. This includes targeting those who may have browsed a product but ultimately did not make a purchase.

Advanced remarketing networks employ display creatives showcasing the specific products that the users had previously shown interest in.

This strategy focuses on a smaller, more defined group of potential customers, allowing for the use of cost-effective advertising placements. Consequently, remarketing ads often yield significantly better post-click conversion rates and return on investment (ROI) compared to other types of display or social media advertising.

Remarketing service providers often use this advantage to encourage advertisers to allocate more budget towards these ads. This is particularly persuasive as, for many advertisers, remarketing represents the only type of display advertising that generates a positive ROI when measured by post-click, last-click conversions.

The issue lies in the fact that results from conversion tracking don’t effectively demonstrate the incremental influence of advertisements, particularly considering that the process of making a purchase is affected by a variety of advertisements and other factors.

Self-fulfilling theory

Remarketing providers frequently assert that remarketing positively influences conversions, even in the absence of clicks, urging advertisers to consider post-view conversions. Yet, this perspective can be misleading.

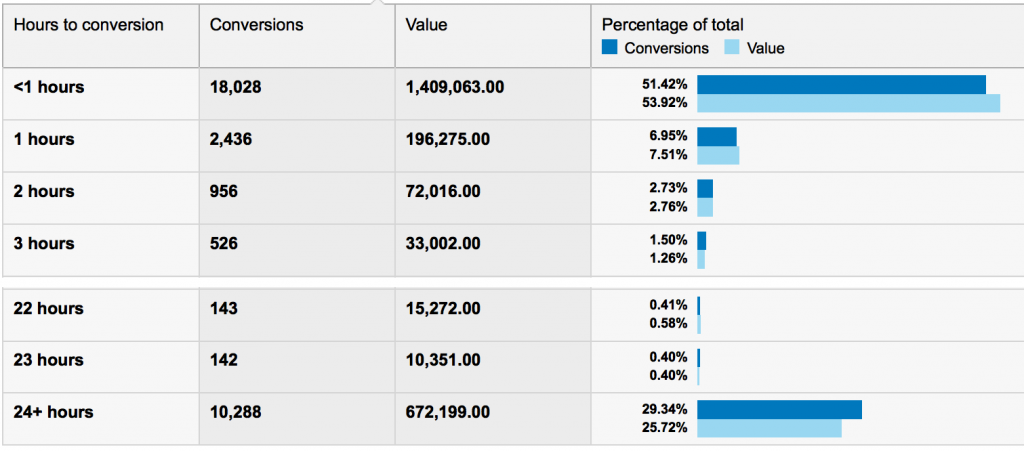

Typically, there’s a noticeable time lag between a click and a conversion, as illustrated in the following example.

Remarketing ads target visitors who have begun the purchase process. While some will click on these ads and complete a purchase, a notable portion would likely have bought the product regardless of ad exposure. Additionally, many users who eventually convert may not view the served ads, yet these instances are still recorded as post-view, or more accurately, post-impression conversions.

Currently, the most advanced web analytics tools fall short in accurately assessing the real attribution of final interactions and the supportive role of clicks and ad impressions/views. The mere presence of an interaction (click or impression) within the conversion funnel doesn’t necessarily prove a positive impact.

Please note that customers often engage with competitor ads during the conversion process. It’s implausible that these interactions enhance sales of our product; they more likely detract from our conversions – although these ads technically exist on the conversion path.

While it’s unlikely that our own ads have a negative impact, the exact contribution they make to conversions remains unclear. Is the attribution 1%, 10%, 30%, or more?

There’s also a possibility that the ads yield a negative return on investment (ROI), primarily if the ad spends money showing ads to visitors who would have purchased the product without ad exposure.

The conversion can’t be 100% attributed to Remarketing can’t b conversions, because it can’t exist without the primary visit from, for example, search engine marketing (SEM), display ads, social media, or email campaigns. Thus, the ROI of post-click conversions from remarketing ads cannot be directly compared with prospecting ads.

Concept of the experiment

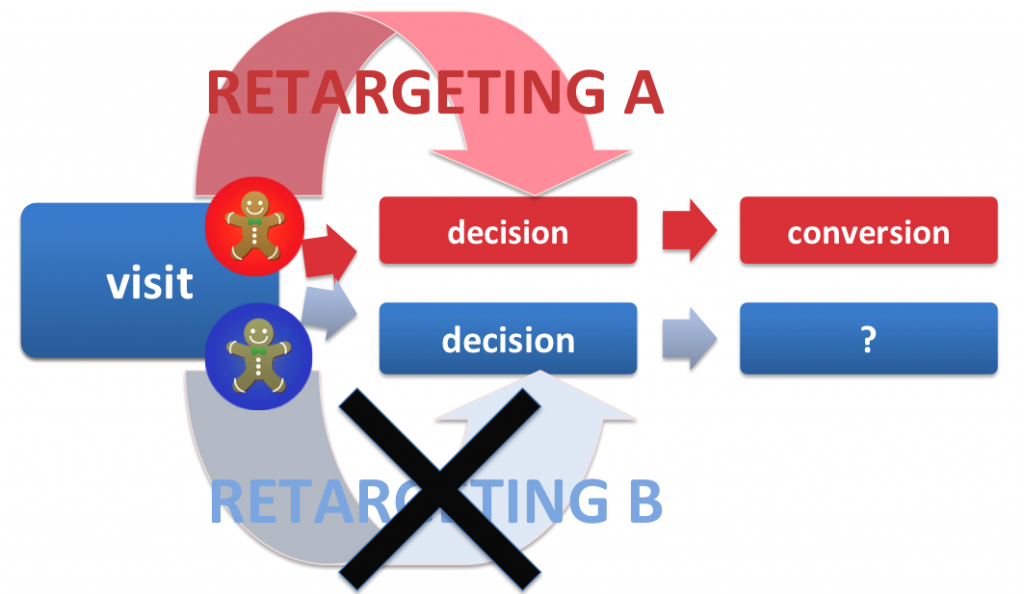

In case of remarketing, we can, however, run an experiment that will show the exact ROI of remarketing campaigns.

We assign to each new user who visited the website, on a random basis, a Google Analytics custom dimension with a value of “A” or “B”. It is a user-scope variable (not session-scope), and re-visit does not overwrite the value.

Then we use Google Analytics remarketing list (custom variable “A” and “B”) and display the remarketing campaign only to the users from the “A” list.

In other words, the potentially retargeted users are divided in two statistically identical populations, “A” and “B”, of which only the population of “A” is subject to remarketing. Comparing conversions in both populations, we will be able to determine to what extent the remarketing has increased the number of conversions.

The stages of the experiment

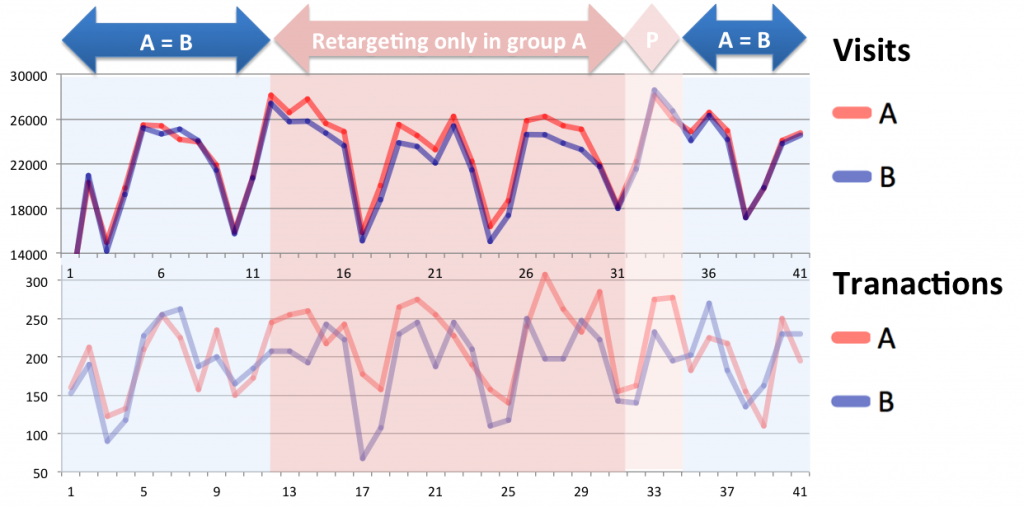

We measured visits and e-Commerce transactions (purchases). The experiment, run on an e-commerce website, was divided into stages:

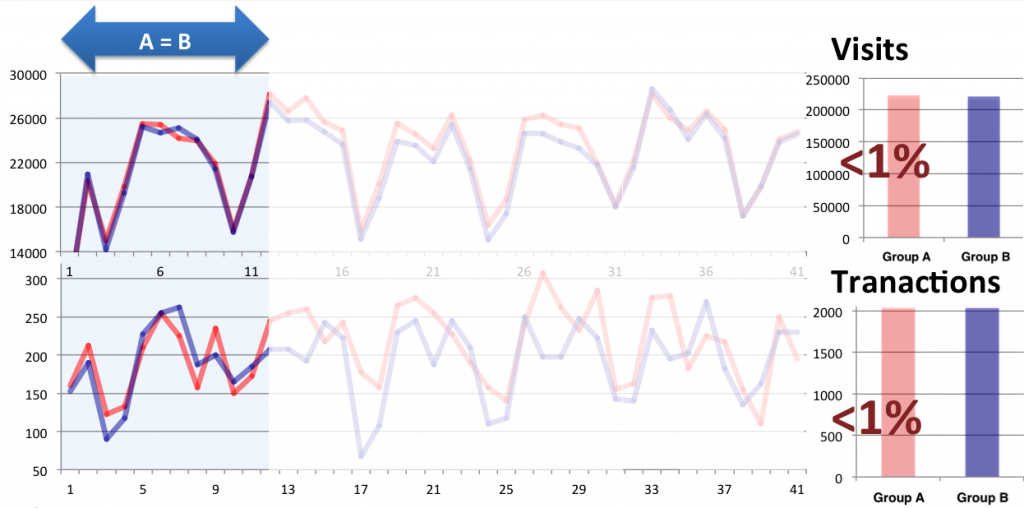

1. A = B – Both “A” and “B” users see remarketing ads.

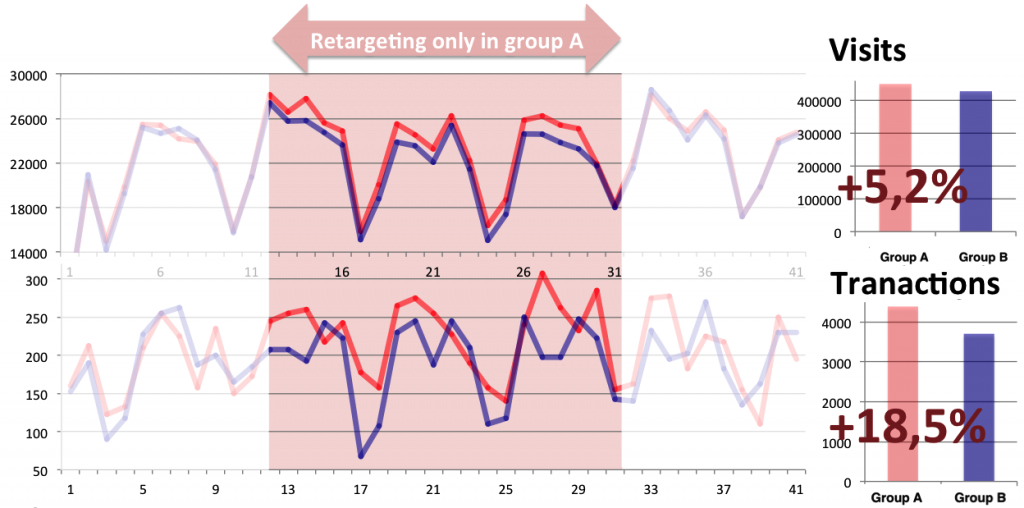

2. Remarketing only in the “A” group – Remarketing in the “B” group has been turned off.

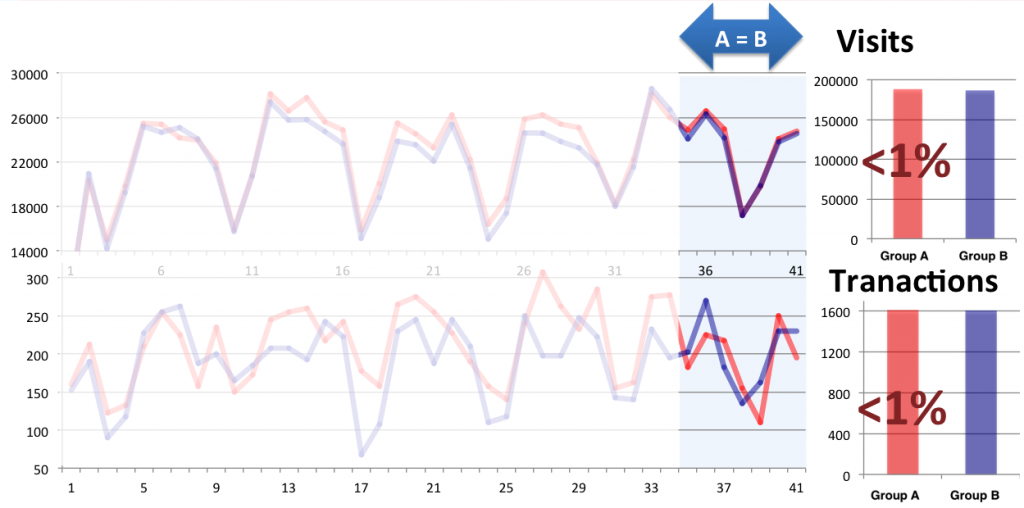

3. A = B – Remarketing for the “B” group has been re-enabled. This stage is split into two parts:

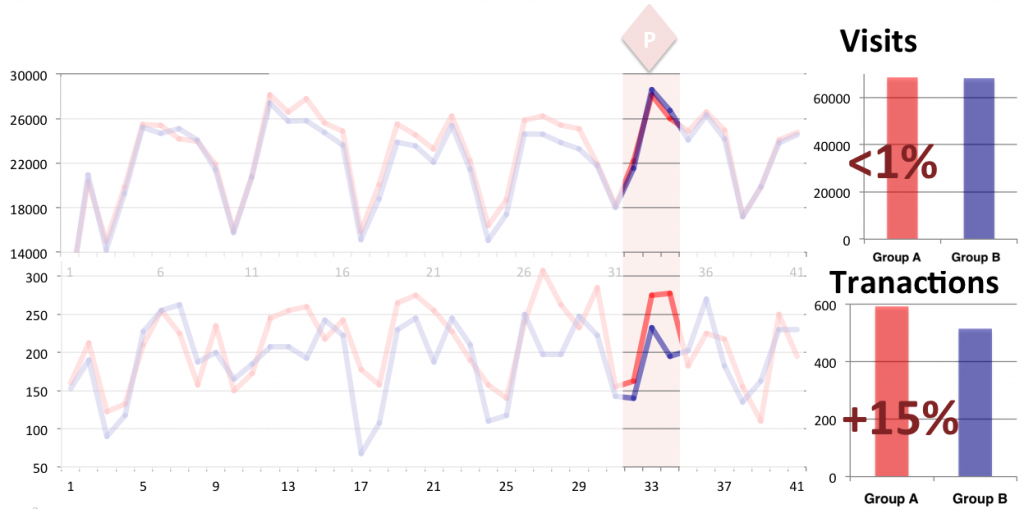

(3a) interim stage (P) – the first three days after “B” remarketing was re-enabled;

(3b) A = B – fourth day and subsequent days.

THE RESULTS

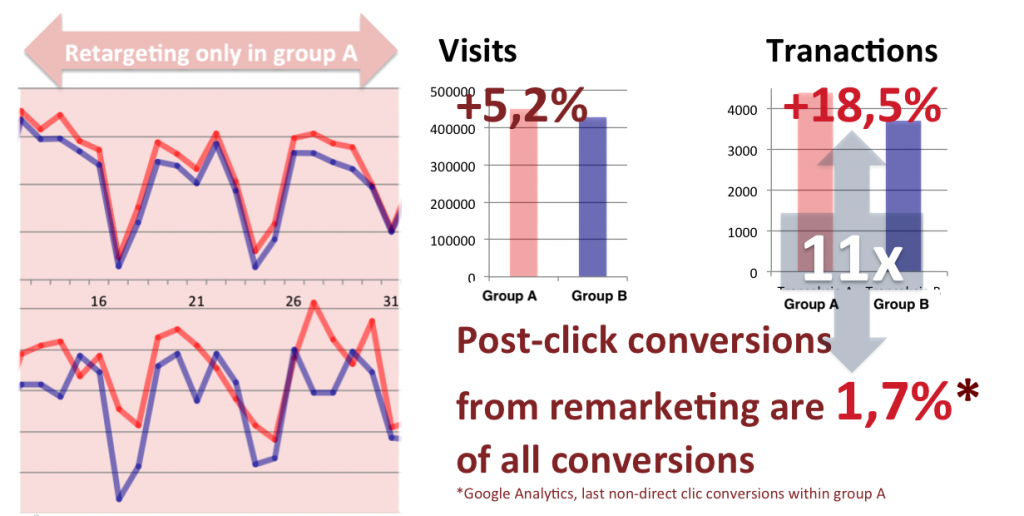

Step 1 (A=B). The purpose of the first step was to ascertain that the two populations of “A” and “B” are statistically identical. Number of visits and transactions in groups “A” and “B” turned out to be almost identical (the difference was much smaller than ± 1%), and other metrics, such as visit duration and pages per visit were almost the same.

Step 2 (only remarketing “A”). After turning off remarketing in the “B” group, we have obviously recorded decrease of visits in the “B” group, and the number of visits in the “A” group was higher by 5.2%. At the same time the number of transactions in the “A” group was higher by 18.5%.

Step 3a (P). Having restored remarketing in the “B” group, the number of visits in “A” and “B” became identical again, but during the first three days, the “A” group had still about 15% more transactions.

Step 3b. On the subsequent days, the number of transactions in “A” and “B” became similar again.

How is this possible? This experiment confirmed that the impact of online advertising is not only click-based. Advertising banners work, even without being clicked. Nobody clicks on the classic TV ad, nobody clicks outdoor or radio ads either, but these ads have impact on sales.

Users who saw remarketing ads made 18.5% more transactions. In the same time, in Google Analytics we could see that the remarketing ads caused only 1.7% of all conversions in the “A” group. So, the actual impact was 11x higher than we could see by observing last non-direct click conversion in Google Analytics.

Interesting observation: during the experiment (Remarketing “A” only), Google Analytics has still reported significant traffic and conversions from remarketing source in the “B” group:

The reason is that Google Analytics assigns a traffic source to the last non-direct visit. Therefore if the user came to website from remarketing, and then, in the course of the experiment, he re-entered the website directly (direct visits), the source of this visit will be still shown as “remarketing” in standard reports. This, actually, shows that the difference between post-click and “real” impact is even higher than 11x.

Summary

In this case, the positive impact of remarketing ads was much higher than the cannibalization. The cost of remarketing ads was much lower than the income from additional 18% transactions. This, however, is not a general conclusion. The result of this experiment can be completely different, depending on:

- product type and the conversion time lag;

- competitive environment – with low competition remarketing may have smaller impact;

- seasonality – the remarketing impact can be different in case of last-minute deals;

- remarketing strategy – Non-optimised remarketing can more likely cannibalise other campaigns.

For this reason, we encourage our clients to conduct this type of experiment individually.