In the world of digital marketing, decisions about budget scaling and campaign optimization should not rely solely on total results — but on marginal effects. Understanding what marginal ROAS and marginal cost per conversion really are can fundamentally change how we make media investment decisions.

What Are Marginal Metrics?

Marginal metrics describe the additional effect generated by the last unit of investment — for example, the impact of the last $1,000 spent on advertising.

Unlike average metrics such as overall CPA (Cost per Acquisition) or total ROAS (Return on Ad Spend), marginal indicators show how effective each additional dollar is — not the overall efficiency of the campaign as a whole.

These are the numbers that reveal whether further increasing the budget is still profitable or whether we’re starting to overpay for each new conversion.

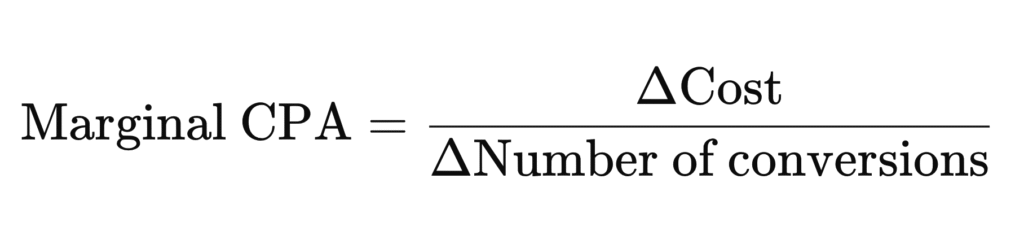

How to Calculate Marginal CPA and ROAS

Marginal CPA (marginal Cost per Acquisition) tells you how much the last conversion cost after the budget was increased.

You can approximate it by analyzing how much the total cost increased relative to the number of additional conversions generated after a small budget change.

If the budget change is large, the last conversion generated will likely be significantly more expensive than the first one — which is why marginal metrics should always be analyzed for relatively small adjustments.

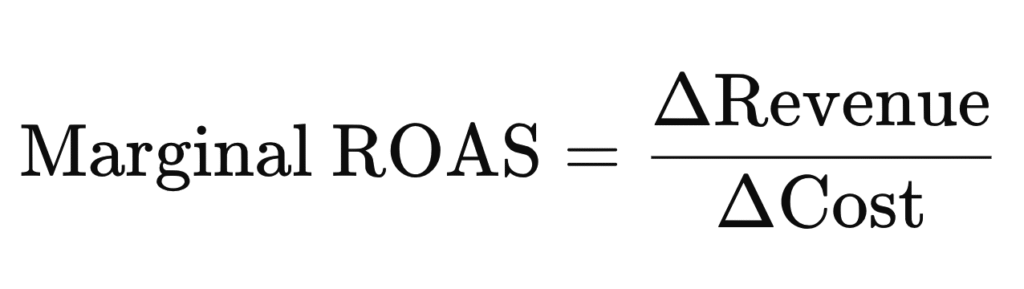

Similarly, marginal ROAS represents the additional return generated by the last portion of your ad spend. It can be estimated by comparing the change in revenue to the change in cost for a small budget increment.

Characteristics of Marginal ROAS and CPA

In most cases, marginal metrics perform worse than average ones. Why?

In auction-based ad systems, campaigns first use the most efficient opportunities — the best audiences, keywords, or placements. Each additional dollar reaches less responsive users, leading to:

- higher marginal CPA

- lower marginal ROAS

This is a natural outcome of the law of diminishing marginal returns — and it applies just as much to marketing as it does to economics.

What This Means for Scaling Decisions

Because marginal metrics are typically worse than averages, you may have a situation where the campaign’s total ROAS is 4 (meaning every $1 spent brings $4 in revenue), but the marginal ROAS for the last $1,000 is only 1.5.

Even if the campaign looks great overall, each new dollar might be generating less and less return — and at some point, the marginal ROAS can drop below your profitability threshold. That’s the point where increasing the budget further no longer makes sense, even if the total results still look good in the report.

Portfolio Bidding and Multiple Traffic Sources — The Trap of Averages

Let’s say we have two traffic sources:

| Source | Conversions | Avg. CPA | Total Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 100 | $50 | $5,000 |

| B | 50 | $80 | $4,000 |

| Total | 150 | $60 | $9,000 |

At first glance, Source A seems much more efficient. Marketers often respond by moving budget from the “worse” source to the “better” one. Let’s see what happens if we do that:

| Source | Conversions | Avg. CPA (after change) | Total Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 105 | $60 | $6,300 |

| B | 40 | $75 | $3,000 |

| Total | 145 | $64 | $9,300 |

Notice that total efficiency actually dropped: the cost increased (+$300), and the number of conversions fell (-5), even though we moved budget from the more expensive source (B) to the cheaper one (A).

How is that possible? Let’s calculate the marginal CPA for both sources:

| Source | Change in Cost (ΔCost) | Change in Conversions (ΔConv) | Marginal CPA = ΔCost ÷ ΔConv |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | $6,300 – $5,000 = +$1,300 | 105 – 100 = +5 | $260 |

| B | $3,000 – $4,000 = –$1,000 | 40 – 50 = –10 | $100 |

Source B actually has a lower marginal cost per conversion, meaning it’s more profitable to move budget from A to B — not the other way around. Doing so yields more conversions (+5) for less money (–$100):

| Source | Conversions | Avg. CPA (after change) | Total Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 95 | $40 | $3,800 |

| B | 60 | $85 | $5,100 |

| Total | 155 | $57 | $8,900 |

Let’s calculate marginal costs for this adjustment:

| Source | Change in Cost (ΔCost) | Change in Conversions (ΔConv) | Marginal CPA = ΔCost ÷ ΔConv |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | $3,800 – $5,000 = –$1,200 | 95 – 100 = –5 | $240 |

| B | $5,100 – $4,000 = +$1,100 | 60 – 50 = +10 | $110 |

As you can see, marginal costs differ slightly depending on whether the budget is being increased or decreased. The more the budget grows, the higher the marginal cost tends to be — hence the difference between $260 vs. $240 for Source A, and $110 vs. $100 for Source B.

The smaller the analyzed budget change, the smaller this difference — and the more precise your estimate of the true marginal cost. It will always be an approximation, but a very useful one.

Finding the Equilibrium Point in a Portfolio

When you’re acquiring conversions from multiple sources, the optimal budget allocation doesn’t necessarily occur when all campaigns have the same average CPA.

If different sources have different marginal CPAs, it’s worth reallocating budget toward those with lower marginal costs.

For instance, if two campaigns both have an average CPA of $100, but one has a marginal CPA of $150 and the other $200, increasing spend by $150 in the first campaign brings one conversion, while decreasing spend by $200 in the second loses one. The total number of conversions remains the same, but you save $50.

The optimal state occurs when all campaigns have the same marginal CPA — meaning that moving budget between them no longer affects the overall result. Their average CPAs may still differ at that point.

Why Marginal ROAS Matters

Understanding and tracking marginal ROAS and marginal cost per conversion is the key to scaling campaigns effectively. Average metrics tell you how performance has been so far — but marginal metrics tell you whether it’s still worth investing further in a given source, or reallocating budget elsewhere.

Grasping these dynamics allows marketers to make more informed, profit-maximizing decisions and allocate budgets more efficiently across channels. It also helps avoid misleading conclusions drawn from average results alone — ensuring budget decisions are based on true incremental value, not historical averages.